Thanks to curator Lily Fürstenow for showing some of my Screen Memories works at Volkssolidarität Berlin in July and August.

Curator Lily Fürstenow poses with Screen Memories works at Volkssolidarität in Berlin Mitte.

News

Thanks to curator Lily Fürstenow for showing some of my Screen Memories works at Volkssolidarität Berlin in July and August.

Curator Lily Fürstenow poses with Screen Memories works at Volkssolidarität in Berlin Mitte.

A selection of works from the 8-bit Nature series is on display at the 'In Bloom' group show at The Drey, Berlin, April 29-May 25.

Thanks to SuperRare for the profile this week in Rare Steals.

Thanks to SuperRare for the profile this week in Rare Steals.

I’m happy to have a work up at Musee Dezentral’s beautiful space in the metaverse. ‘Bacchus and Ariadne’ can be seen at the 21 second mark.

Have you been interested in art since your childhood?

Yes, I was first introduced to art when my parents took me to the Vatican at 6 years old. On that same trip I started collecting postcards of Italian mosaics and buying small space Lego sets. I also received the stamp collection of my late Italian grandfather, whom I never knew. In a lot of ways, my aesthetic sensibility was formed during this time and has remained fairly consistent until today. I still make drawings of old space Lego boxes and stop in my tracks when I see a postcard showing a bird in a mosaic. I was also an obsessive trading card and comic collector. I would stare at these objects for hours on end when I was a teenager.

How have you developed your career? Was it something that just happened or did you make strategic decisions?

It’s all been strategic decisions, although luck plays a role. Unless you're rich or well connected, there’s no real easy path to becoming an artist. I come from a small city in Canada—Saskatoon, Saskatchewan—so I’ve spent most of my adult life pursuing opportunities to make my name. You really have to be determined. I first moved to Montreal, and then to Toronto, and five years ago I moved to Berlin, where I’m very happy to be based. Persistence and a ‘never give up’ attitude is crucial.

That all being said, at the end of the day, it’s about the work, and there’s nothing that can improve your odds more than making great work. Nevertheless, I believe art should be treated as a business like any other, which means having an entrepreneurial mindset. Luck alone is rarely enough.

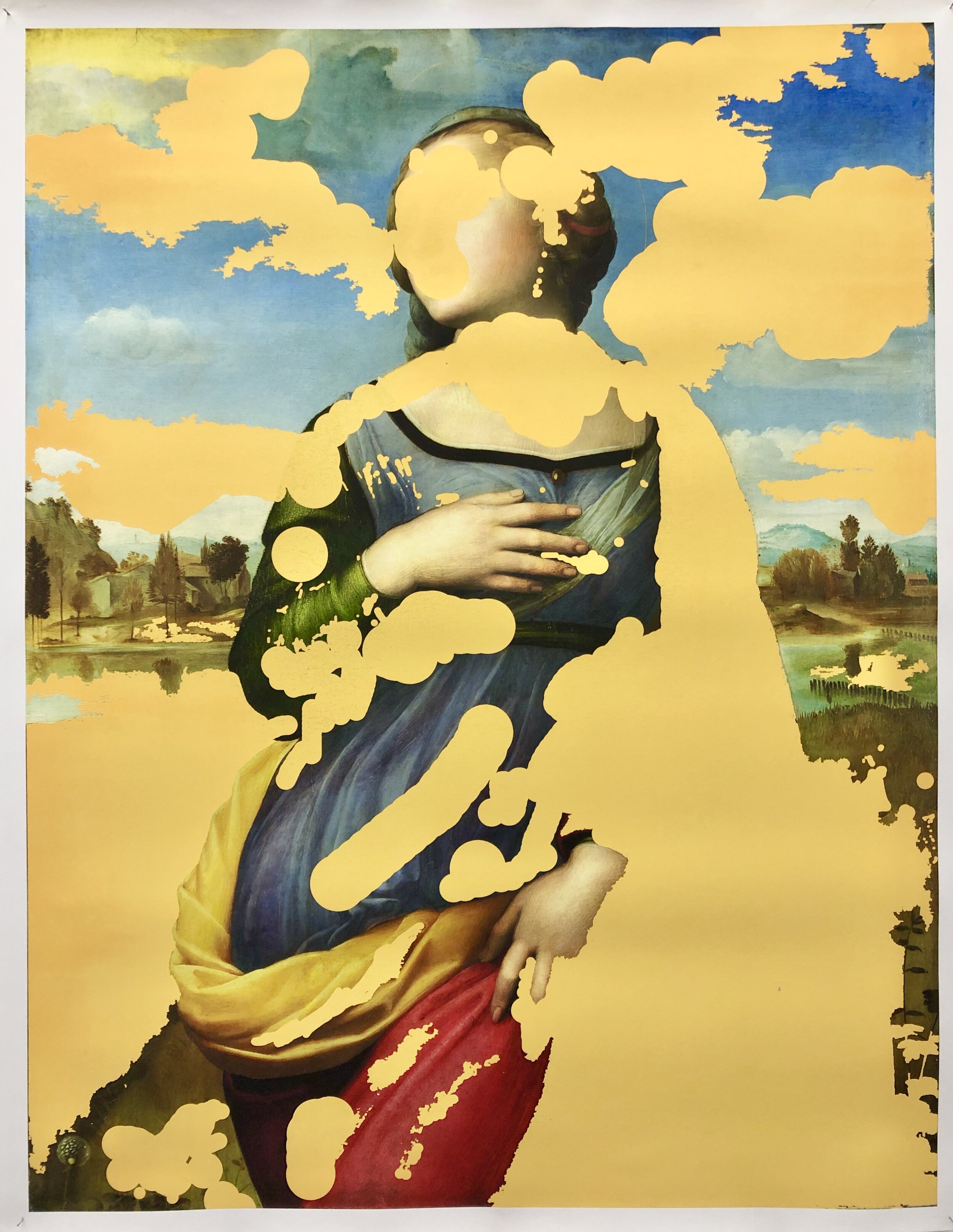

How did you came up with the idea of making "Galatea"?

That’s part of my Screen Memories series where I take well known paintings and cover up areas with digital shapes and fills. The idea originally started a couple of years ago with basic fills that I would add on top of screenshots of famous paintings using my iPhone. As the project developed over time, I began to add and remove some of the layers in Photoshop, which created a strange mix of organic and inorganic shapes, and over time, I’ve refined the method.

From a conceptual point of view, Galatea is a tribute to the women in my life who all seem to be working so hard to keep their families and their jobs going, while also maintaining their health. It’s an image of a triumphant, powerful femininity, so it seemed appropriate. I use a lot of Raphael’s work because of his unparalleled use of colour as well as his rich compositions. To see Raphael’s work in person really is an otherworldly experience, and I recommend it to everyone. To have a full understanding of art requires an encounter with Raphael. It’s real-world magic.

Further, I see the history of art as a dialogue among artists. And to be a part of the tradition, you have to be in conversation with the tradition. If you read Chaucer or Blake, you’ll find endless references to other writers and the history of ideas. This is part of what makes them great artists. So, I directly reference art history in order to enter that conversation.

Is there an artwork that you are most proud of? Why?

One of my favourite pieces is Car Ad #2, which is one of my very early iPhone works from 2016. This showed me that the phone could be a serious tool for art making. I love David Hockney, but I think the phone has far more capabilities than acting as a kind of virtual paintbrush. It’s more akin to a sampler to make hip hop and techno, and I treat it that way.

Otherwise, it’s usually whatever I’m working on. I’m always trying to get better and develop new breakthroughs. It’s important to try and do things that are slightly out of your reach because you achieve this goal more often than you might think—maybe 20% of the time—and that’s pretty good.

On most of your art, you use red and yellow paint, what is the story behind your choices?

Those colours happen to work well with a lot of the paintings that I paint over. It’s primarily an aesthetic decision, although sometimes, say in the case of the red Caravaggios, there’s a symbolic overtone.

Who are your biggest influences?

My biggest influences are writers. I wrote my master’s thesis in English literature on J.G. Ballard’s The Atrocity Exhibition, which is an experimental novel. Interestingly, Ballard’s biggest influences were visual artists, primarily the Surrealists, so it’s full-circle in a sense. The psychedelic philosopher Terence McKenna also had a big influence on me—he has a mixed legacy, but he reminds us in a very persuasive and insightful way that we basically have no idea what’s going on. This is very important and something we easily forget.

What is your scariest experience in your professional life?

The sense that you may have screwed up your life. That feeling when you wake up at 3 am and think, “Have I made a huge mistake?” Things have been going well recently, so I don’t have that feeling as often, but sometimes you wonder. Pursuing the artist’s path will test your soul...repeatedly. In a sense, it can be a massive sacrifice of one’s life, depending on how things turn out.

What is your dream project?

I’ve never thought of it before, but doing something in the Vatican, which I consider to be a kind of temple to the mind. That would be the pinnacle.

What is the best piece of advice you can give to an artist just starting out?

Focus on one thing at a time. If you have a part-time job, do your art first before your other work. Be practical—think of who might buy your work from the beginning. This can actually improve your work. And put in the hours — don’t worry about failure — the road to success is paved with failure. The important thing is that you put in the time and stay focused.

I’m very pleased to be a part of The MetaFrame’s new campaign showcasing digital artists within their posh new digital art frame. Check out their feed to see a nice overview of some of the most interesting artists in the space.

Special thanks to the team at Siemens Arts Program for the opportunity to speak on NFTs and the future of digital art. The discussion was broadcast live on Twitter and can be seen below.

Thank you @Pocobelli @mirko_ross @TylerCohenWood @EvanKirstel for the controversial debate and the practical tips for future NFT artists. For those who missed our #NFT webinar, the broadcast is still available!!! 👉💾🖼️ https://t.co/IPLBzJoaC7

— Anke Bobel (@AnkeBobel) April 22, 2021

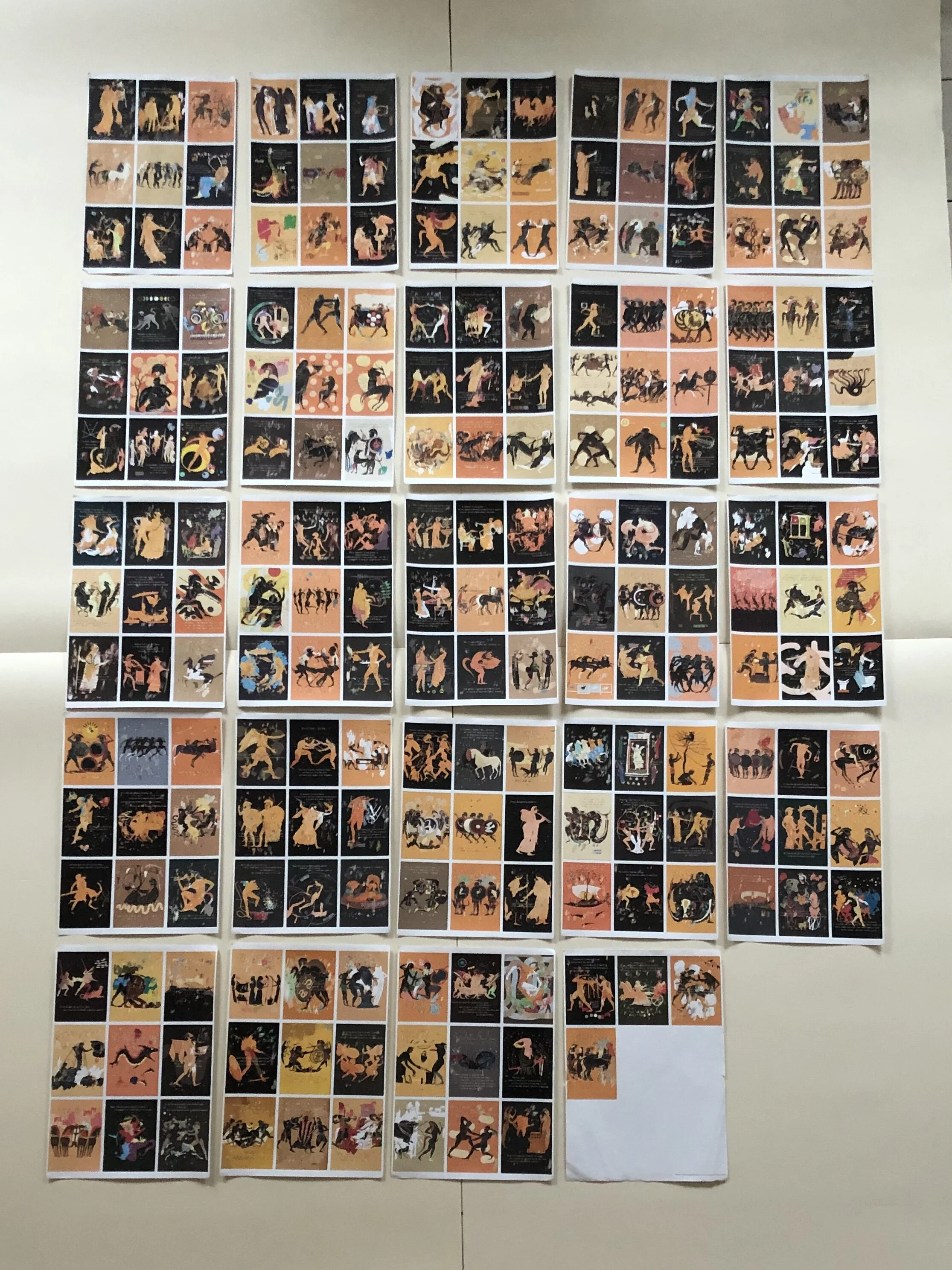

I was pleased to see one of my works on the cover of SuperRare’s weekly update for March 19, 2021. It’s been a crazy month in the crypto art market, with NFTs going mainstream and sales going through the roof, so it was a great honour for one of my Peloponnesian War artworks to be included in the week’s highlights. Thanks guys.

I was pleased to have a studio visit with independent curator Valentina Galossi, who had many interesting comments and ideas. Check out her book, ‘The Life of Artists in Berlin’. She also does artist interviews on her Instagram channel. Thanks Valentina!

Following last month’s show at Fata Morgana in Berlin, the Leo Kuelbs Collection is now showing a virtual exhibition of Screen Memories online. Visit Leo Kuelbs Collection website for more information and view the virtual exhibition here:

https://artspaces.kunstmatrix.com/en/exhibition/3772082/adrian-pocobelli-screen-memories

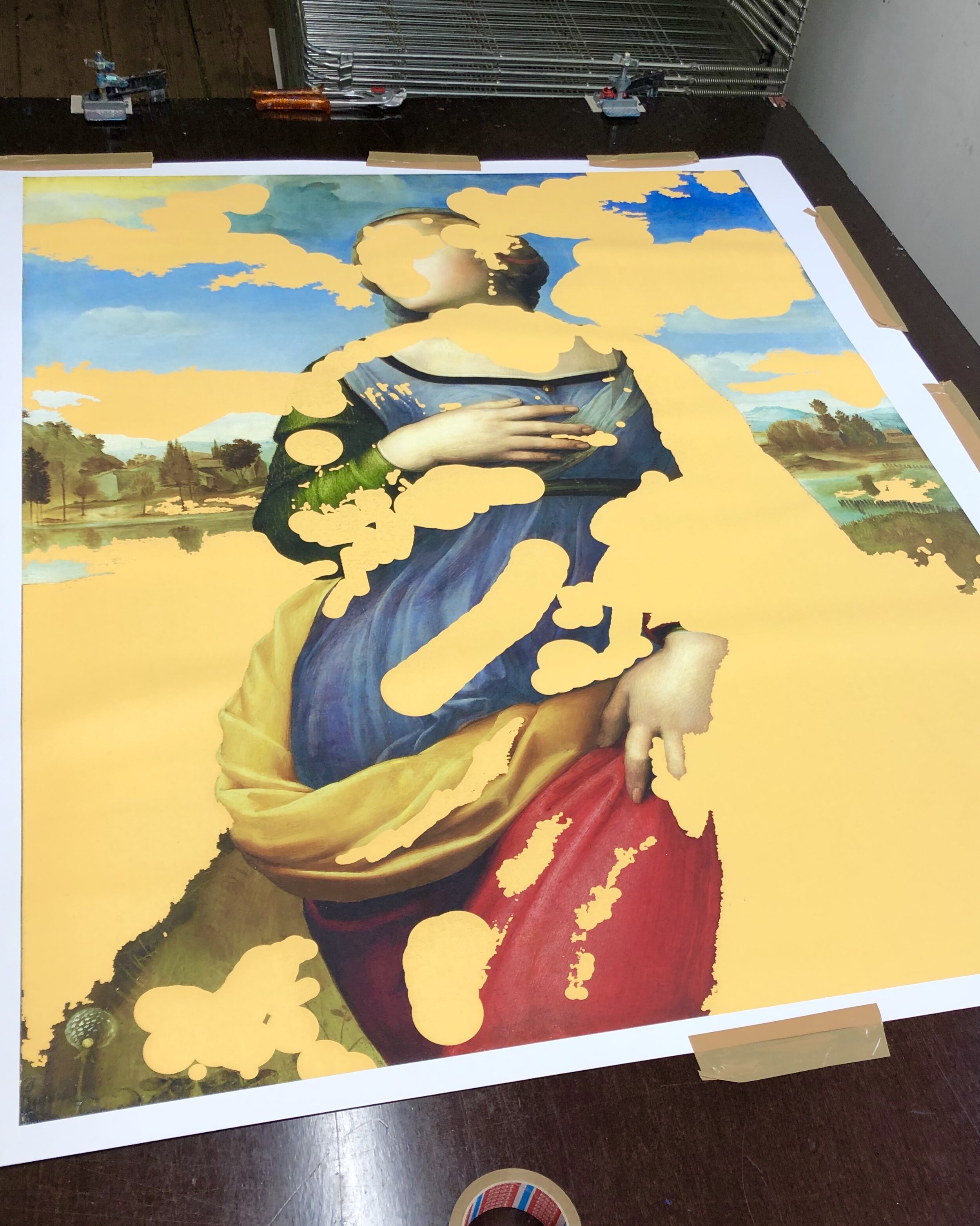

The making of ‘St. Catherine of Alexandria’ at BBK’s Bethanien studios in Berlin.

Quinton Delcourt is a design student from France who is taking a six-month course in Berlin. As part of his assignments, Quinton interviewed a local artist.

Quinton Delcourt: Where are you from?

Adrian Pocobelli: I’m from Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, which is in Canada’s midwest. After that I moved to Montreal for eight years, and then I lived in Toronto for four years before moving to Berlin.

QD: What was your first job? What did that bring to you?

AP: My first job was working in a comic store. I spent so much time there they finally just gave me a job. I spent a lot of my early teenage years just staring at comic covers in my bedroom — I would lay them all out in a row and just stare at them. Then I would rearrange them and stare at them some more. This had a big impact on me — I consider many comic covers to be as interesting as many modern paintings. The covers were very important to comics — as Stan Lee said, 90% of sales in the 1960s were based on the cover.

QD: How did you know you were going to make art?

AP: I visited the Vatican when I was 6 years old and during the trip I started collecting postcards of old Roman mosaics of birds, the kind you might find in Ravenna. That was the first thing I ever collected. I just loved to stare at them. I kind of knew then that this is where I would focus.

QD: When did you start making art?

AP: Since I was a kid — once in a while I would copy a Leonardo landscape, for example, at a pretty young age. For a few years when I was a teenager I wanted to become a comic artist, but I always kind of knew I wanted to do something visually poetic, so I gravitated back to visual art.

QD: How are you working? What are your inspirations?

AP: I generally make compositions using drawing apps on my phone, and then I find ways of reproducing the work in the physical world — often I’ll print on canvas or paper and paint on top of it with acrylic paint.

My main inspirations are writers, J.G. Ballard, the great British Surrealist writer who wrote Crash, and Terence McKenna, who I consider to be one of the most imaginative philosophers of the 20th century, even though he gets very little respect from academia. As far as artists are concerned, I quite like Richard Prince’s recent work, and David Hockney is always interesting.

QD: When and why did you move to Berlin?

AP: I went to Berlin to pursue my artistic vocation. In Canada it’s very difficult if you don’t go to the right art schools — maybe that’s true everywhere. I’ve had a few solo shows at project spaces since I moved here three years ago, so the city has been good to me.

QD: What are the advantages in Berlin for art ?

AP: There’s an active community of people who are enthusiastic about art here — most of them artists — and you get some world class contemporary art galleries here — all with fairly affordable rent, although that’s changing all the time. I consider Berlin the last affordable art capital in the Western world, which is why I’m here. I’m also a fan of German electronic music, which had a big influence on me when I was younger. I appreciate the German spirit.

QD: What is the message in your art?

AP: I’m trying to do visual philosophy when I make art. In a sense, the last thing I’m interested in is drawing from a model or painting an outdoor landscape. My biggest concern is juxtaposing iconography from our shared visual vocabulary. I believe that associating visual ideas that are far apart can produce new ways of thinking and give bigger perspectives on reality. In a sense, it’s in the Surrealist tradition, based on Lautreamont, of fusing two opposite realities in a new context, but pushed further.

QD: I see you use nearly the same color palette, but I see an evolution in your work. Can you talk to me about that?

AP: I’m very intuitive when it comes to colour. I’ve been told I mix a lot of hot and cool colours, which I find a little bit amusing. I don’t even think about colour in those terms. I think my use of colour is one of the things that makes me most unique — I also think a bit of my Italian heritage comes out in my palette. It’s all intuitive.

QD: Moreover you play with typography, different sentences or mathematical formulas. Can you talk about that also?

AP: Yes, this is an example of the visual philosophy that I was talking about. The Surrealists took the content of external reality and mixed and matched it in unusual and inspired ways, while often distorting the scale. I’m applying this logic to the screen, mixing words, images and number — math, symbolic logic, computer code, etc. — every signification system that I can think of — and juxtaposing them.

QD: Do you have any other things you want to tell me?

AP: I believe it’s important to focus on the things that make you and your imagination unique. In other words, embrace your uniqueness and sail full speed into your imagination.

QD: Thank you so much!

“Reality is more like a novel than Newtonian three-dimensional space.”

— Terence McKenna

We live almost our entire lives in our imaginations, as most thinking is inherently a creative act, but, like fish in water, the imagination remains largely invisible to us, and so we diminish its significance. We pay lip service to it and acknowledge its virtues and importance as a wellspring of creativity, but we ultimately dismiss it as an unreal place that has no real ontological status. At best, we give it a nebulous secondary status in relation to pre-eminently important and ‘real’ material reality.

The success of science has compounded our ontological bias towards external reality. As physics, chemistry and biology delve deeper into the nature of matter and the laws that govern life and the universe, we are seduced into thinking that we are achieving a relatively comprehensive model of reality. This is further supported by the near-magical success of technology, which, like confirmation bias in a social media filter bubble, reaffirms our scientific, externally oriented worldview with each passing success, each greater than the last.

However, as many have pointed out, consciousness, or mind, remains stubbornly unaccounted for. Philosophy can provide a science-friendly, epiphenomenal explanation for consciousness — that consciousness emerges at higher levels of complexity as a novel property — yet from the scientific vantage point, the nature of consciousness — what it is — remains uncompromisingly mysterious, slippery and full of uncertainty, as the inner world of subjective experience — so far — has never been measured, and likely never will be. As a result, it seems inevitable that a scientific modelling of consciousness will remain forever incomplete.

Most philosophers and scientists concede this point, describing the inability of science to account for subjective experience as an “explanatory gap” — that the best results from the brain sciences will inevitably leave out vital information about subjective experience. This results in what is called “the hard problem of consciousness”, which refers to the difficulty in explaining why and how physical processes give rise to conscious experience. But are we correct in trying to use science to account for something that appears to exist, phenomenologically, in a separate dimension from three-dimensional space?

Prominent philosopher of consciousness David Chalmers, who gave a popular TED Talk on consciousness in 2014, and spoke on the subject at Google Talks on April 2, 2019, suggests we need to engage with ‘radical ideas’ and develop a ‘new physics’ that incorporates mind into our scientific models of the universe. In his TED Talk, Chalmers outlines three prevailing science-friendly views of consciousness: 1) That mind is a fundamental component of the physical universe alongside matter, space-time and charge. 2) Panpsychism, the theory that consciousness is a universal property of all systems, and by extension, matter, which would mean, for example, photons would have consciousness, however minutely. 3) Integrated Information Theory, originated by neuroscientist Giulio Tononi, which posits that the amount of consciousness a thing contains is commensurate with the complexity of a given system and can be represented as a precise mathematical quantity, measured in ‘phi’, or Φ.

Science remains incapable of accounting for consciousness

All of these concepts, nevertheless, remain predictably unsatisfying, as they are all trapped in the old physics paradigm. In other words, these theories are trying to reduce consciousness, or subjective experience, to the corporeal world, where mind has a quantitative measure and a location in physical space, e.g. “There’s a plant. It contains a certain amount of consciousness.” Scientific materialists want to begin with matter and derive consciousness from it because this is the paradigm from which they view the world. However, this is akin to looking for lost keys in a well-lit area because it’s easier to see there.

The truly radical viewpoint is to let go of science and metaphysics as the sole credible explanatory methods to understand consciousness. The metaphysics of Neoplatonic philosopher Plotinus (205–280) would say the exact opposite of these three views: it’s not soul in body, but body in soul (V.5.9). So who is right? The scientific method doesn’t allow for the exploration of incorporeal realities, while the ratiocinations of metaphysics can be argued persuasively in each direction. But is reason enough? After 2,500 years of speculation on the nature of mind, panpsychism is basically a rehashed, scientifically-palatable term compiled of ancient Greek philosophical notions found in Thales, Anaxagoras, Plato, Aristotle and the Stoics, and has not fundamentally brought us any closer to an understanding of what consciousness is and how it is produced. Science and metaphysics have a role to play in understanding consciousness, but they are insufficient on their own. In other words, consciousness is too big of a problem for the intellectual sandboxes of science or philosophy to deal with.

A new approach: Pataphysics and its definitions

I propose a different framework to understand consciousness — and to model knowledge — using pataphysics. French playwright Alfred Jarry (1873–1907) coined the term pataphysics, for which he gave several definitions in his novels and plays, most prominently in Exploits and Opinions of Dr. Faustroll, Pataphysician (1911). Here are the four main definitions:

1. Pataphysics is the science of imaginary solutions.

2. Pataphysics is the science of that which is superinduced upon metaphysics, whether within or beyond the latter’s limitations, extending as far beyond metaphysics as the latter extends beyond physics.

3. Pataphysics will examine the laws governing exceptions, and will explain the universe supplementary to this one.

4. Pataphysics will be, above all, the science of the particular, despite the common opinion that the only science is that of the general.

As a pioneer of absurd theatre, Jarry may have been half-joking when he used the term, yet the concept resonates, and there is nothing stopping us from taking it seriously and even pataphysically redefining it to suit our purposes, as there is a need for a larger umbrella term that incorporates metaphysics, science, as well as the qualitative knowledge that comes through fiction in literature and the arts.

Why pataphysics does what metaphysics can’t do

The reason we need pataphysics and not simply metaphysics is because metaphysics is preoccupied with true and false, real and unreal, and this causes it to ignore the significance of anything which it deems unreal. Metaphysics and philosophy are trying to know and understand reality. Pataphysics isn’t metaphysics; rather, pataphysics is a science (episteme) of story. Pataphysics isn’t as preoccupied with the distinction between fact and fiction. Everything is narrative, and, as such, has its own validity. The existence of narrative is ontological evidence in itself. We may decide that some stories are not very valuable, but not simply because they’re ‘anecdotal’.

Story is the prime matter of consciousness

Consciousness is built-in with a narrative producing power (dynamis), i.e. the imagination, which may be more widespread across nature than we might realize. This story-building function is what illuminates our understanding of the world and gives it significance. Without story there is no meaning, no reason, and no understanding. The nervous system processes and understands reality through narrative; therefore, we should consider narrative itself as our primary tool for modelling reality. Because of story, we can have knowledge, and in the context of consciousness, there is no simpler element. Story is the eldest form of knowledge. Every conceptual system, real, fake or otherwise, requires narrative to exist. Even mathematics equations are narratives, whether they’re correctly solved or not.

Ultimately, narrative, or story, is the prime matter of consciousness. Without story there is only raw sense perception. Everything begins and everything ends with story. It is inescapable and it permeates all living things. Our very DNA is a story that gets transmitted through genes and bloodlines. The nature of consciousness, nature and reality, insofar as we understand it, is storytelling. We are stories embodied.

Natural science would have a more accurate place in the system of knowledge

This would not dismiss science — it would simply rearrange our hierarchy of knowledge in a way that would position science in a more accurate place within our knowledge systems — as our best tool, or storytelling method, for modelling and manipulating material reality — rather than trying to force it to provide answers on subjects, such as consciousness, which it can’t answer. We should return to thinking of science as ‘natural science’ and not use it as the sole determiner of knowledge about reality, which is where we seem to have arrived.

We have to understand consciousness on its own terms, which is that it exists in a story-generating medium. Just like the stuff of the physical universe is matter, the stuff of consciousness is story. If you want to understand what something is, you have to understand how it works, so the most natural way to understand consciousness is to try to come to a deeper understanding of the core nature (physis) of story — what ideas are, and how they bind themselves together. This is the path to understanding consciousness.

What is narrative? What bonds ideas together? Do each of the senses create their own consciousness?

I propose that any two ideas, no matter how disparate, when placed in association, form narrative. An idea can be defined as a unit of information that can be conceptualized; in other words, anything that can be defined. Each definition is a story, and, in that respect, story should be recognized as a self-referential system.

Two units of meaning, or ideas, bonded together produce narrative. For example, on their own, ‘red’ and ‘table’ are ideas. Together, ‘red table’ is the beginning of a narrative. Narrative begins even before verbs are introduced. As the Surrealists demonstrated, any two ideas, when juxtaposed, are enough to produce narrative.

Ideas can be joined using different types of bonding:

1. Logic — most stories, fiction and non-fiction, are created using logical associations of one kind or another. These chains of reason help give stories coherence.

2. Juxtaposition — Any two ideas, no matter how different, when placed side by side, will begin to create narrative. The imagination can’t help but associate meaning between ideas. The Surrealists understood this on a profound level, which is why their central axiom was the joining of two disparate realities in a new context. This was the ultimate conceptual response to the Age of Reason.

3. Overlapping — this requires a visual or an aural medium, such as painting or music, to perform. Overlapping ideas on top of each other is an advanced form of juxtaposition: instead of simply placing things beside each other they are placed on top of each other.

It’s possible that each of the senses creates its own consciousness. We think of thinking itself as consciousness, but visual consciousness may have a different set of principles from aural consciousness (likely the source where our thinking came from) and smell, taste and touch. It’s possible that nature’s creative element, i.e. the imagination, works through the sensory apparatus, which may grow consciousness neurogenically as the senses receive more diverse information from external stimuli. Synaesthesia is a kind of consciousness that is created when these modes of awareness bleed into each other.

Everything is narrative; time to give up notion that true is real and relevant, and false is untrue and insignificant

If the goal of knowledge systems, such a science and metaphysics, is to provide accurate models of reality, who has given us a clearer, more detailed picture of consciousness, James Joyce or David Chalmers? Our current scientific paradigm doesn’t provide for qualitative forms of knowledge, such as those found in the arts, while metaphysics is locked in a rationalistic paradigm in its quest to determine the nature of reality and to distinguish fact from fiction.

Science or philosophy could argue that Christianity is full of falsehoods, and that it can be easily dismissed epistemologically, but should there really be no place for Christianity in our knowledge systems? Doesn’t it say something about reality? What about literature? Don’t we learn about ourselves, human nature and the world by reading great works of literature? Where does this currently fit in our system of knowledge? Does metaphysics provide an adequate framework to formally integrate literature and the arts into our knowledge systems? Do we simply ignore astrology and alchemy? These are pataphysical systems. Religions are pataphysical systems — metaphysics are pataphysical systems — pataphysics really is that which is superinduced on metaphysics.

Science would no longer be the sole arbiter of reality; how do we ascribe value to stories?

But what makes some stories more valuable than others? Science uses material reality, and deservedly holds a special privileged status among knowledge systems, but it’s also limited by its materialistic focus. Religions, on the other hand, may lack scientific credibility, but their influence on large populations over long periods of time have given them status as stories of importance. One could argue ‘distribution’ and ‘duration’ are variables that ‘measure’ the influence, and hence the value, of a story. However, this doesn’t say anything about whether a story is true or not.

The work of Sigmund Freud, for instance, has only been around 125 years (duration), but his thinking is almost wholly integrated into the lexicon of the Western mind (distribution). So even if Freud is wrong about basic principles (or even everything), like Christianity, his system still has value as a useful, provisional model and a story of historical importance, even if it isn’t believed. These are modes of understanding the world, and, again, even if they’re ‘wrong’, it doesn’t mean that they have no use. They are grandiose imaginative structures — paradigms — that interpret the world from a specific and developed viewpoint.

Pataphysics is a qualitative science

The real solution to consciousness lies in consciousness itself, just like the real solution to physics lies in three-dimensional physical reality. Phenomenologically, we are stories first and physical human beings second. The production of story by the imagination may be a widespread, elementary characteristic of nature and perhaps even the key to free will (another seemingly unsolvable riddle for science and philosophy). Nature is creative, and the imagination is our direct line to nature’s creative energy. So pataphysics, the science of imaginary solutions, needs to turn its eye on the inner theatre of our minds, using all of the techniques that the human imagination has to offer, science, metaphysics, fiction, math, statistics, art and whatever other storytelling method makes sense.

Pataphysics is also a way to recognize the value of non-rational, non-empirical knowledge. A science of speculation, a qualitative science, might model the irrational knowledge one would find in reading histories, literature and looking at artworks and juxtapose them with science, statistical analysis and philosophical reasoning. The one quality all knowledge systems have is that they are all made of story. Pataphysics, the science of imaginary solutions, is the only term with a large enough scope to incorporate and group all knowledge systems. Jarry cryptically wrote, “Pataphysics is the science.” And it seems Jarry, once again, was weirdly right, knowing what we should have known all along: The ultimate science is story.

Q. Lei wrote a nice post on her website about 'The Peloponnesian War' art book. It's always interesting to see how people respond to the work, as sometimes you can get so deep into these things that you start to have no idea what other people might think about it. Anyway, very interesting and beautifully written (good title, too) – thanks Lei!